Photo: Martin Schmitt

Two global communities with closely related values

By Marcos Cramer

Having discovered Unitarian Universalism less than five years ago, I now feel at home in this liberal religious community. One of the reasons for this feeling is that as a UU I am part of a global community of shared values. This community both confirms my fundamental ethical values and expands my horizons through personal exchange and constantly new perspectives. In the course of coming to to know the global UU community, I have also discovered many similarities and parallels to another global community, namely the Esperanto community, in which I have been active for almost twenty years and where I also feel at home.

Having discovered Unitarian Universalism less than five years ago, I now feel at home in this liberal religious community. One of the reasons for this feeling is that as a UU I am part of a global community of shared values. This community both confirms my fundamental ethical values and expands my horizons through personal exchange and constantly new perspectives. In the course of coming to to know the global UU community, I have also discovered many similarities and parallels to another global community, namely the Esperanto community, in which I have been active for almost twenty years and where I also feel at home.

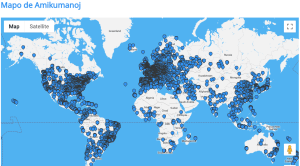

Esperanto is a language that was conceived in the 1880s to be used as a second language for international communication. It is far easier to learn than other foreign languages because its grammar has no exceptions and it has a flexible system for forming new words based on existing words. Already before the First World War, a worldwide Esperanto community was formed – today this community is present in over 120 countries and actively uses the language for international friendships, travel and intercultural exchange. In recent years, Esperanto has experienced a new boom, as international communication got simplified through the Internet.

When Esperanto was published in 1887, French was still the most important language for international communication, but it was by far not as widespread as English today. Since the 70s of the 20th century, the widespread use of English has shifted the community’s attention away from the goal of making Esperanto everyone’s second language towards enhancing the already existing use of Esperanto for intercultural exchange in a global community. Furthermore, the Universal Esperanto Association and its national branches strongly support the rights of oppressed linguistic minorities.

The Sixth Principle of Unitarian Universalism is the goal of world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all. By making the three goals of peace, liberty and justice universally applicable to all of humanity, this principle has given rise to a new understanding of the term Universalism, which complements the historical meaning of Universalism as the theological position of universal salvation.

To me the sixth principle seems an almost perfect formulation for the so-called internal idea of Esperanto, which serves as a common ethical foundation for many Esperanto speakers since the early years of Esperanto. Since the Esperanto community is first and foremost a linguistic community and not explicitly a community of shared values, one does however find in its ranks a larger spectrum of different values than within the global UU community. But there are also many other similarities apart from the sixth principle of the UUA: relatively many Esperantists are guided by humanistic values, while relatively many Unitarians and Universalists value intercultural exchange positively. And it is probably no coincidence that both among Esperantists and among Unitarian Universalists there is an exceptionally high level of acceptance and support for traditionally oppressed minorities such as LGBTQ people and racial minorities. Furthermore the founder of Esperanto, Ludwik Lejzer Zamenhof, already had religious and humanist ideas that were very similar to those of today’s Unitarian Universalists, despite the fact that he probably never had any contact with the Unitarians and Universalists of his time, but developed these ideas based on liberal Judaism.

The following article by the President of the Spanish Esperanto Federation explains very well the common values shared by many Esperanto speakers. The title of the article refers to the concept of universalism as discussed above.

Another Universalism

by José Antonio del Barrio

by José Antonio del Barrio

In recent times, various world events have shown changes in the way people address globalization and have demonstrated that several aspects of the organization of world relations do not meet the needs of normal people. In some cases the attempted solutions have led to the growth of nationalism and tensions between peoples. The world seems to move towards an increase in hatred and intolerance.

Some may think that the problem is globalization itself, but I and many others believe that the fault lies in the way in which international relations have been organized, through the hegemony of one culture, one nation, one geographic area, and as an evident symbol of this hegemony, also the dominance of one language as the basis of globalization.

However, another globalization is possible, one in which people can feel equal and have equal rights, in which the respective great powers do not impose their cultures to the rest. Our universalism and our desire to approach humanity, without borders and barriers, must overcome this crisis, because they are not to blame for the flaws in the current process.

A good example that another solution is possible is the continuity and vibrancy of the international language Esperanto. For many years it has been an effective tool for communication among people around the world, without the need to abandon one’s own language, and without this feeling that we all experience when we speak the languages of another people: The feeling that our situation is inferior. When we speak Esperanto with other people, we feel that we have a common ground, that we are equal, and that we can experience feelings of friendship that transcend the borders that separate us.

Esperanto is a perfect demonstration that another way of connecting to the whole world is possible, and that universalism and the sense of community among the people of the planet are still valid, but that we need to find another way to organize it. Now is not the time to create more walls, we just have to find other ways to overcome the present ones.

You must be logged in to post a comment.